Update: Diane Seuss was announced the winner of the Pulitzer Prize in poetry on May 9, 2022, for her work frank:sonnets.

April is National Poetry Month, an especially busy time for Diane Seuss ’78, a Kalamazoo College alumna and professor emerita who taught in the English department and served as writer in residence for three decades. With accolades rolling in for her latest book and a new collection of poetry on the horizon, Seuss is marking the month with virtual readings across the country and reflecting on the successes and challenges of the past two years, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, the John Updike Award and the COVID-19 pandemic.

As a 2020 Guggenheim Fellow, Seuss joined a prestigious group of scholars and artists who have received grants from the Guggenheim Foundation to help provide fellows with blocks of time to work with creative freedom. The Foundation receives about 3,000 applications each year and awards about 175 fellowships.

In 2021, Seuss received the John Updike Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The biennial award recognizes a mid-career writer who demonstrates consistent excellence.

The Guggenheim and Updike awards have helped Seuss, who grew up in rural schools and earned a master’s degree in social work rather than an M.F.A. in creative writing, feel a hard-won sense of authority as a poet.

“They’re both very prestigious,” Seuss said. “While you would hope that you could feel that you have a right to be heard without that recognition, it sure helps. It’s amazing that I was this kid with a single mom in Niles, Michigan, writing poems in typing class, and truly, through sheer persistence and a lot of luck, I have managed to be here.

“frank: sonnets,” in 2021.

“For me and others like me, people in the margins for whatever reason, such recognition is an encouragement. It’s saying, your work has worth. It makes all the difference to be seen and heard and acknowledged.”

Seuss published her fifth collection of poetry, frank: sonnets, in 2021. The book, from Graywolf Press, is currently a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Poetry, was named a finalist for the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, and won both the PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Prior to frank: sonnets, Seuss published four other poetry collections: Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl (Graywolf Press, 2018), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Los Angeles Times Poetry Prize; Four-Legged Girl (Graywolf Press, 2015), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize; Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open (University of Massachusetts Press, 2010), recipient of the Juniper Prize; and It Blows You Hollow (New Issues Press, 1999).

frank got its start during a writing residency at Willapa Bay Artists in Residence near Oysterville, Washington.

“A lot of people had said, ‘You should write a memoir because you’ve had quite a life,’” Seuss said. “You know what is beneath the surface when folks say you should write a memoir! I took that idea with me to the residency, but I just couldn’t hear the memoir in prose.”

During the residency, Seuss took a day trip to Cape Disappointment, where visitors can hike to a lighthouse on a cliff. The drive was beautiful, but when she arrived, Seuss felt exhausted and took a nap in the backseat of her rental car before simply returning to her cottage.

“On the drive back, I started narrating what had just happened,” Seuss said. “I had this line in my mind: I drove all the way to Cape Disappointment, but didn’t have the energy to get out of the car. It’s past tense, but it’s just-happened past tense. Then it came into my head, I’m kind of like Frank O’Hara.”

A prominent poet who died in 1966, O’Hara wrote kinetic, lively poems encompassing his present thoughts and actions, which he called “I do this, I do that” poems. “By the time I got back to my little cottage, I had these lines jotted down on a pad. I saw, this could be divided into 14 lines; this could be sonnet length. Then I thought, Wow, I could write a memoir in sonnets, and they could be composed under the influence of Frank O’Hara, who was so improvisational and spontaneous.”

The poems in frank are contemporary American sonnets, Seuss said, mostly unrhymed but with some vestige of rhyme and meter and a couplet at the end. She employs the tension between the high-end poetic form of the sonnet and her working-class language and storytelling. At the same time, she draws on parallels between the working-class mentality of being economical and the economy of language inherent in the sonnet’s 14-line limit. As one of the poems says, “The sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do / without.”

The title references poet Frank O’Hara as well as serving as an homage to Amy Winehouse and her first studio album, Frank. It also refers to frankness itself, a quality omnipresent in the sonnets.

“I’m not writing like I’m a role model,” Seuss said. “I talk a lot about really tough mistakes in my life. I own my stuff. I see myself pretty clearly. I hope that people who read it feel that their lives, too, have value, and that they can be honest about who they are without shame.”

frank is a memoir, but not a traditional or linear one. “It tells the story of my life and my interior, but from shifting perspectives and with a range of approaches to language,” Seuss said.

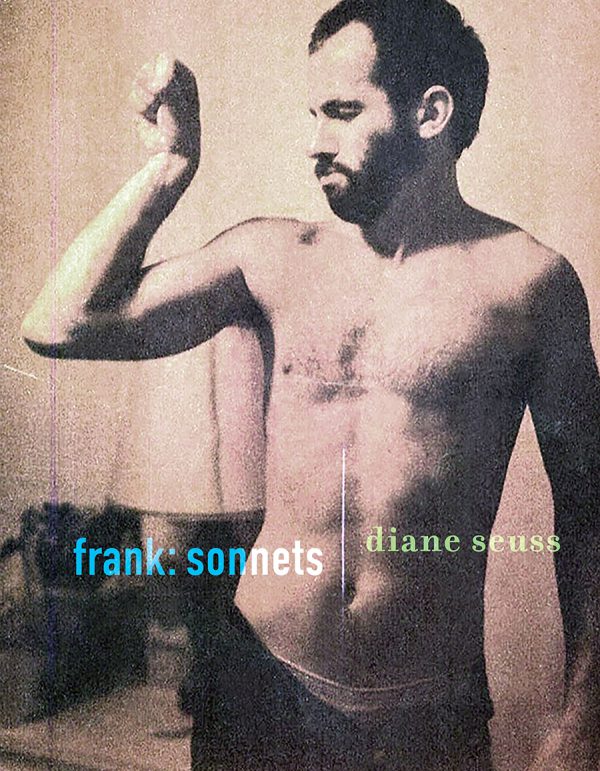

One section is in the voice of the rural town where Seuss grew up; one is transcribed from text conversations with her son. Several sonnets involve a dear friend, pictured on the cover, who died of AIDS in the ‘80s. Her father, who died when she was 7, appears in some poems, and her mother, a single mother from then on, features prominently. One poem, on the back of a center fold out, is written by her son.

“I think of the book in a lot of ways as a collaboration,” Seuss said. “The book, especially its cover photo, has received attention in countries throughout the world. Maybe especially during the pandemic, readers responded to a collection that values a single life, but also the communities and individuals that contribute to any one life.”

The COVID-19 pandemic hit shortly after Seuss received the Guggenheim fellowship, scrapping her original plans for a fellowship project involving in-person research and interviews in her hometown of Niles. Post-frank, the roots of that project have grown into her forthcoming sixth collection of poetry.

“My intention was to be able to go back to my hometown for considerable periods of time and do research, specifically around a legal case that happened in the town involving abuse at a daycare center that really cut the town in half,” Seuss said. “The roots of that project are still there, but I ended up opening the book up to larger questions about what poetry can be up against trauma, loss and our current reality.”

The original project and title, “Little Epic,” ended up as a single, longer poem in the new collection. Seuss had been interested in developing a connection to Latin poet Catullus and his longest poem, Catullus 64, an epyllion or “little epic.”

“It tells the story of a wedding among the gods by reading the images on a coverlet that is given to the bride,” Seuss said. “I loved that idea and wanted to pull it forth into the story of my town.”

K Professor of Classics Elizabeth Manwell proved a “fantastic resource” for Seuss’ efforts to learn more about Catullus and classical poetry in the process of writing “Little Epic.”

The new book is tentatively titled Modern Poetry, “which is kind of an audacious claim in itself for a book of poems,” Seuss said. The title poem is about her first poetry class at K with her mentor, Conrad Hilberry, who sought her out after giving honorable mention to a poem she wrote in high school typing class, entered into a contest for Michigan poets by Seuss’ guidance counselor. Hilberry encouraged her writing, helped her do readings in classes and eventually supported her in finding the resources to attend K.

“That class at K in 1974 also opened the pathway to what the rest of the book is, in quotes ‘about,’ if books are about, and that is poetry itself,” Seuss said. “I lived through the ongoing pandemic, aware of so much loss and suffering, of course, and for me, experienced in isolation. I’m divorced; my son is in the upper peninsula. My mom and the rest of my family are all still in Niles. My dog was my soulmate and he died during the pandemic. Through most of the pandemic, I have been in my house, right across from campus, with nobody.

“I kept asking myself this question, what can poetry be now? What is poetry now? That really is the defining question of this next book. To explore that, I went back to the roots of my education in poetry.”

Seuss also forced herself to abandon the sonnet and take a different formal approach in Modern Poetry.

“You can only do one thing so long,” Seuss said. “I’m writing the longest poems I’ve ever written, in free verse. The new work takes a certain kind of authority, a willingness to take up that much space and to think through some things about poetry itself, and to weigh in. Authority has always been an issue for me as it is for so many people who come from the margins, whether it’s race, class, gender, orientation or identity. I think some of the best teachers come from marginal realities; eventually, you may come to that place where you realize that your perspective has value.”

“In my teaching at K, in my teaching since leaving K as well as in my writing, I have wanted to communicate the value of individual realities.”

From frank: sonnets, copyright © 2021 by Diane Seuss. Used by permission of Graywolf Press.

There is a certain state of grace that is not loving.

Music, Kurt says, is not a language, though people

say it is. Even poetry, though built from words,

is not a language, the words are the lacy gown,

the something else is the bride who can’t be factored

down even to her flesh and bones. I wore my own

white dress, my hair a certain way, and looked into

the mirror to get my smile right and then into my own

eyes, it’s rare to really look, and saw I was making

a fatal mistake, that’s the poem, but went through

with it anyway, that’s the music, spent years in

a graceful detachment, now silence is my lover, it does

not embrace me when I wake, or it does, but its embrace

is neutral, like God, or Switzerland since 1815.

From the forthcoming Modern Poetry, Graywolf Press, 2024.

Originally published in Chicago Review’s Memoir Dossier, January 28, 2022.

Poetry

There’s no sense

in telling you my particular

troubles. You have yours too.

Is there value

in comparing notes?

Unlike Williams writing

poems on prescription pads

between patients, I have

no prescriptions for you.

I’m more interested

in the particular

nature and tenor of the energy

of our trouble. Maybe

that’s not enough for you.

Sometimes I stick in

some music. I’m capable

of hallucination

so there’s nothing wrong

with my images.

I’m not looking for wisdom.

The wise don’t often write

wisely, do they? The danger

is in teetering into platitudes.

Maybe Keats was preternaturally

wise but what he gave us

was beauty, whatever that is,

and truth, synonymous, he wrote,

with beauty, and not the same

as wisdom. Maybe truth

is the raw material of wisdom

before it has been conformed

by ego, fear, and time,

like a shot

of whiskey without

embellishment, or truth lays bare

the broken bone and wisdom

scurries in, wanting

to cover and justify it. It’s really

kind of a nasty

enterprise. Who wants anyone

else’s hands on their pain?

And I’d rather be arrested

than advised, even on my

taxes. So, what

can poetry be now? Dangerous

to approach such a question,

and difficult to find the will to care.

But we must not languish, soldiers,

(according to the wise)

we must go so far as to invent

new mechanisms of caring.

Maybe truth, yes, delivered

with clarity. The tone is up

to you. Truth, unabridged,

has become in itself a strange

and beautiful thing.

Truth may involve a degree

of seeing through time.

Even developing a relationship

with a thing before writing,

whether a bird

or an idea about birds, it doesn’t

matter. But please not only

a picture of a bird. Err

on the side of humility, though

humility can be declarative.

It does not submit. It can even appear

audacious. It takes mettle

to propose truth

and pretend it is generalizable.

Truth should sting, in its way,

like a major bee, not a sweat bee.

It may target the reader like an arrow,

or be swallowable, a watermelon

seed we feared as children

would take up residency in our guts

and grow unabated and change us

forever into something viny

and prolific and terrible.

As for beauty, a problematic word,

one to be side-eyed lest it turn you

to stone or salt,

it is not something to work on

but a biproduct, at times,

of the process of our making.

Beauty comes or it doesn’t, as do

its equally compelling counterparts,

inelegance and vileness.

This we learned from Baudelaire,

Flaubert, Rimbaud, Genet, male writers

of the lavishly grotesque.

You’ve seen those living rooms,

the red velvet walls and lampshades

fringed gold, cat hair thick

on the couches,

and you have been weirdly

compelled, even cushioned,

by them. Either way,

please don’t tell me flowers

are beautiful and blood clots

are ugly. These things I know,

or I know this is how

flowers and blood clots

are assessed by those content

with stale orthodoxies.

Maybe there is such a thing

as the beauty of drawing near.

Near, nearer, all the way

to the bedside of the dying

world. To sit in witness,

without platitudes, no matter

the distortions of the death throes,

no matter the awful music

of the rattle. Close, closer,

to that sheeted edge.

From this vantage point

poetry can still be beautiful.

It can even be useful, though

never wise.