Project (SIP) as part of a research study on exercising

fruit flies at Wayne State Medical School.

While many student-athletes at Kalamazoo College are interested in health and wellness, there might only be one who has applied that interest not only to sports, classes, externships and travel, but also to fruit flies.

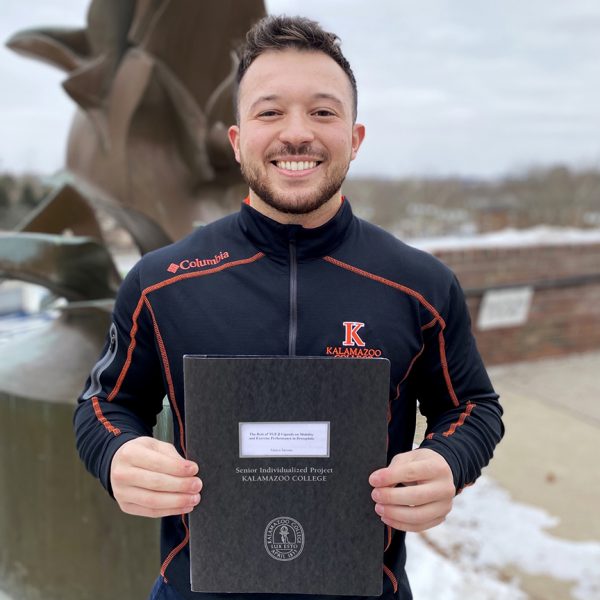

Marco Savone ’22 is a chemistry major and Spanish minor on the pre-med track who played football at K for four years. His first year at K, he completed an externship refining nutrition plans for a local health company. COVID-19 scrapped his study abroad plans, but he was able to make a medical volunteering trip to Costa Rica.

In summer 2021, Savone completed his Senior Integrated Project (SIP) by participating in a three-month research study at Wayne State Medical School with exercising fruit flies.

“It sounds bizarre at first,” Savone said. “They’re one of the very few labs in the country that does this. They want to apply the fruit fly model to human models because fruit flies have about 60 percent of their genome similar to humans and share many genes that are related to those in the human exercise response. Their goal is to be able to apply what they find with fruit flies to mice and rodents, and eventually human studies with exercise physiology.”

Fruit flies also make good test subjects because they are cheap and have short lifespans. Within 60 days, researchers can see the effects of exercise over a full lifespan.

“Humans live a long time so it’s hard to look at a human model in regards to how exercise affects the health span,” Savone said. “Ideally you would need a longitudinal study.”

part of a medical volunteer trip to Costa Rica.

Savone took part in a study exploring the relationship between exercise and two gene-encoded proteins, myostatin and follistatin, that are involved in muscle mass development. Through a process called RNAi, or gene silencing, one group of fruit flies had myostatin basically eliminated in their systems, while a second group underwent the same process with follistatin.

Within each group, Savone exercised one sub-group and did not exercise another.

“We had lots of vials and they were all labeled with stickers,” Savone said. “We had this machine that would move the vials up and then they would drop down, and when the flies would feel the impact, they would fall to the bottom of their vial and then they would start climbing up to the top. This process would be repeated to act like a treadmill for the flies.”

The team would measure the speed and endurance of the fruit flies over time.

“One overarching thing that I did find was that we did see exercise responses with the two groups of flies,” Savone said. “We tested them for how long they would basically run, how fast they would fatigue. Then we also looked at their climbing speed to see how fast they would climb up their vial and we did see that exercise improved climbing speed and endurance.”

While Savone experienced some success, he also learned from setbacks in the research. The RT-PCR test to verify how much of each gene was expressed in the fruit flies did not work, and Savone had to pivot to another type of testing.

student-athlete for the lessons he learned

in teamwork, leadership and time management.

“I was really bummed that it didn’t work out,” he said. “But I was told by my mentor that it’s a hard thing to get used to and you need a lot of practice. I didn’t feel as bad when he told me that.

“Research is so unpredictable. You have to learn how to troubleshoot when something goes wrong, and there are so many outcomes that can happen. There may be one singular thing you want to find, but you may find different things you didn’t even expect to see. That was really eye opening for me.”

Savone sees immense benefit in gaining hands-on research experience outside of K to bring back and apply to classwork. He also benefitted from mentorship and collaboration with the lab staff, mainly Ph.D. students, and from a presentation he gave at Wayne State that boosted his confidence when presenting his SIP at the chemistry symposium.

His experiences at Wayne State also came into play in January, when Savone started a short-term contracted position with Kalamazoo lab Genemarkers, LLC, which had pivoted during the pandemic from skincare-product testing to COVID-19 testing.

His job involved separating test tube vials and preparing them for RT-PCR testing, the same type of testing he had attempted on the fruit flies at Wayne State. Savone also helped chart data for the tests.

“They were just starting to train me on other things, but unfortunately, since I was a contract employee, they had to let me go when the COVID numbers went down significantly,” Savone said. “It was interesting to see how that whole process works behind the scenes of the COVID testing and it was a rewarding experience.”

After graduating this June, Savone plans to study for the MCAT in the summer and take at least two gap years to work in clinical research before attending medical school, perhaps back at Wayne State.

Looking back on the past four years, Savone sees how far he’s come. He credits his growth to the academics at K, his hands-on experiences at Wayne State and Genemarkers, and the lessons in teamwork and time management he learned as a student-athlete.

“My experiences wouldn’t have been possible without going to K,” Savone said. “If I had to redo the whole thing again, I would do it the same.”