When scientists perform research, what they discover is often proprietary and kept in close confidence until results are published or patented. Erin Somsel ’24, however, would rather share her research with the world.

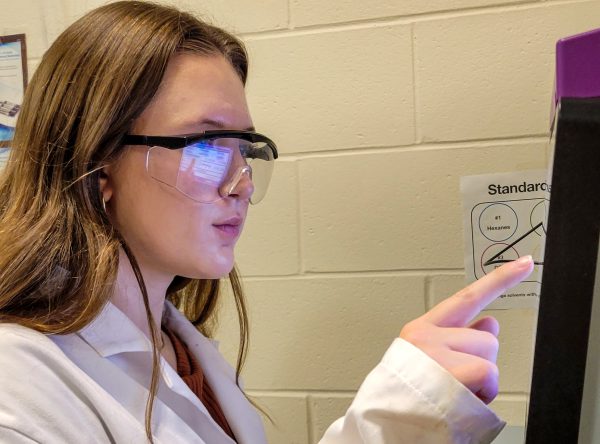

Somsel, a biochemistry major at Kalamazoo College, is working on her Senior Integrated Project with Associate Professor of Chemistry Dwight Williams and the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, which engages top students from about 25 global institutions in research through the Open Synthesis Network. Their combined efforts provide shared, open-source information, allowing entire teams to look into the molecules and compounds that present the most promise for developing medicines that fight neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).

NTDs are a diverse group of 20 conditions that disproportionately infect women and children in impoverished communities with devastating health, social and economic consequences. Many are vector-borne with animal reservoirs and complex life cycles that complicate their public-health control. Plus, drug companies often don’t see the benefits of helping impoverished communities that are less profitable.

The open-source initiative, though, is more interested in cooperative work and says its participating researchers have developed 12 treatments for six deadly diseases, potentially saving millions of lives.

“That’s appealing to me because there are scientists from everywhere that work on this project,” Somsel said. “I think that’s a cool way of getting everyone involved in the scientific community to come up with a solution to a big problem.”

Somsel hopes her work will contribute to a treatment for a seventh affliction, Chagas disease. The inflammatory condition is most common in South America, Central America and Mexico with rare cases in the southern United States. It spreads through the feces of a parasite often called the kissing bug, as it damages the heart and other vital organs when the bug bites humans.

“A lot of the work on the drugs for Chagas disease was done in the 1960s, so there’s an urgent need for new ones,” Somsel said. “Chagas has two phases, acute and chronic. The acute phase has common symptoms such as fever, headache and fatigue, but if it turns chronic, it can cause cardiomyopathy and serious gastrointestinal problems. The drugs only work in the acute phase, so if it’s not caught, it’s life-threatening. There’s also no vaccine against Chagas disease.”

In the lab, IC50 values represent the concentrations at which substances inhibit parasites through biological and biochemical processes. The hope is to find IC50 values through molecules and compounds that warrant further research.

“I’ve been working on optimizing our processes and I got the procedure down so that we could start generating some of the compounds that we wanted to,” Somsel said. “The next step is to continue building the library of the chemicals we want to make and send them into the Open Synthesis Network, where it will test them for the activity against the parasites.”

Somsel first was introduced to NTD research when she was on study abroad in Costa Rica. While there she studied Latin American health care systems, including Costa Rica’s, in an environment that challenged her to grow.

“I think K has a unique culture of pushing students beyond their comfort zone,” she said. “I don’t think that I would have had that experience at any other place.”

Now, with that experience—plus a K-Plan that involves student organizations such as the Health Professions Society and the Sisters in Science, athletics through the women’s soccer team, and academics as a teaching assistant for introductory chemistry—Somsel feels like she’s prepared to one day succeed in medical school, where she will continue pursuing lab research. Hopefully, that will involve further research involving NTDs.

“Success for me used to be going to class, getting A’s and stuff like that,” Somsel said. “Then, I started working in the lab. I found that there are many little things that build up to success. When I had a reaction that wasn’t successful, it was easy for me to say, ‘I was unsuccessful today.’ But Dr. Williams helped me put it in a different perspective. He could say, ‘No, you were unsuccessful in generating this compound, but you were successful in realizing this solvent didn’t work, so we can try something else and move forward.’ I think that has really shaped me as a student. It helped me understand that if at first something doesn’t work for me, I’m going to keep trying and persisting to find something that does.”