Kalamazoo College has appointed six faculty members as endowed chairs, recognizing their achievements as professors. Endowed chairs are positions funded through the annual earnings from an endowed gift or gifts to the College. The honor reflects the value donors attribute to the excellent teaching and mentorship that occurs at K and how much donors want to see that excellence continue.

The honorees are:

- Espelencia Baptiste, the Arcus Center for Social Justice Leadership Senior Faculty Chair

- Anne Marie Butler, the Arcus Center for Social Justice Leadership Junior Faculty Chair

- E. Binney Girdler, the Dow Distinguished Professor in Natural Sciences

- Sohini Pillai, the Marlene Crandell Francis Endowed Chair in the Humanities

- Dwight Williams, the Kurt D. Kaufman Endowed Chair

- Daniela Arias-Rotondo, the Roger F. and Harriet G. Varney Endowed Chair in Natural Science

Espelencia Baptiste, Anthropology-Sociology

Baptiste is currently on sabbatical in Benin where she is working on a book project focused on different ways Africans and Haitians claim each other across time and space. Her research focus centers on the relationship between Africa and its diasporas. She has been active and engaged within the College since her arrival; most recently, she received the College’s Outstanding Advisor Award in 2023 and served as Posse mentor from 2019-2022.

Her courses include Lest We Forget: Memory and Identity in the African Diaspora, You Are What You Eat: Food and Identity In a Global Perspective, Communities and Schools, and Missionaries to Pilgrims: Diasporic Returns to Africa. Within her teaching, she is invested in challenging students to imagine the production of power, particularly as it relates to belonging, as a continuous phenomenon.

Baptiste has a bachelor’s degree from Colgate University, and a master’s degree and Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University.

Anne Marie Butler, Art and Art History; Women, Gender and Sexuality (WGS)

Butler has a joint appointment in Art History and Women, Gender, and Sexuality. Her research focuses on contemporary Tunisian art within frameworks of global contemporary art, contemporary global surrealism studies, Southwest Asia North Africa studies, gender and sexuality studies, and queer theory. At K, she teaches at the intersection of visual culture and gender studies, instructing courses such as Art, Power and Society; Queer Aesthetics; Performance Art; and core WGS classes, and this is her fourth season as volunteer assistant coach for the swimming and diving team at K.

Butler is co-editor for the volume Queer Contemporary Art of Southwest Asia and North Africa, which will be available in October (Intellect Press). She has been published in ASAP/Journal, Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies, and The London Review of Education. She is also an editor for the volume Surrealism and Ecology, expected in 2026.

Butler has a bachelor’s degree from Scripps College, a master’s degree from New York University and a Ph.D. from the State University of New York at Buffalo.

E. Binney Girdler, Biology

Girdler is the director of K’s environmental studies program and a biology department faculty member. She focuses on plant ecology and conservation biology with her research involving studies of the structure and dynamics of terrestrial plant communities.

Girdler previously had an endowed chair as the Roger F. and Harriet G. Varney Endowed Chair in Natural Science. She develops relationships with area natural-resource agencies and non-profit conservation groups to match her expertise with their research needs and the access needs of students. In 2022, she and K Associate Professor of Biology Santiago Salinas contributed to a global research project that proves humans are affecting evolution through urbanization and climate change. The study served as a cover story for the journal Science.

Girdler commonly teaches courses titled Environmental Science, Ecology and Conservation, and Population and Community Ecology along with an environmental studies senior seminar. She earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Virginia, a master’s degree from Yale University and a Ph.D. from Princeton University.

Sohini Pillai, Religion

Pillai is the director of film and media studies at K and a faculty member in the religion department. She is a comparatist of South Asian religious literature, and her area of specialization is the Mahabharata and Ramayana epic traditions.

Pillai is the author of Krishna’s Mahabharatas: Devotional Retellings of an Epic Narrative (Oxford University Press, 2024), a comprehensive study of premodern retellings of the Mahabharata epic in regional South Asian languages. She is also the co-editor of Many Mahabharatas (State University of New York Press, 2021) with Nell Shapiro Hawley and the co-author of Women in Hindu Traditions (New York University Press, under contract) with Emilia Bachrach and Jennifer Ortegren. Her courses have included Religion in South Asia; Hindu Traditions; Islam in South Asia; Dance, Drama, and Devotion in South Asia; Religion, Bollywood, and Beyond; Jedi, Sith, and Mandalorians: Religion and Star Wars; and Princesses, Demonesses, and Warriors: The Women of the South Asian Epics.

Pillai has a Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley; a master’s degree from Columbia University; and a bachelor’s degree from Wellesley College.

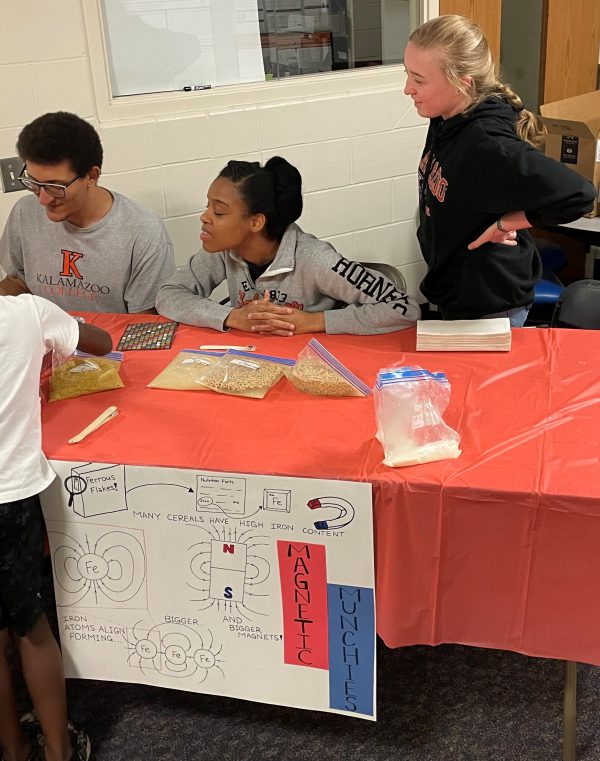

Dwight Williams, Chemistry and Biochemistry

Williams previously was an endowed chair at K, having served as the Roger F. and Harriet G. Varney Assistant Professor of Chemistry from 2018–2020. He teaches courses including Organic Chemistry I and II, Advanced Organic Chemistry and Introductory Chemistry. His research interests include synthetic organic chemistry, medicinal chemistry and pharmacology.

Williams spent a year as a lecturer at Longwood University before becoming an assistant professor at Lynchburg College. At Lynchburg, he found a passion for the synthesis and structural characterization of natural products as potential neuroprotectants.

Williams learned more about those subjects after accepting a National Institutes of Health postdoctoral research fellowship at the Virginia Commonwealth University Medical College of Virginia Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology. During that fellowship, he worked in medicinal chemistry and pharmacology, where his work was published in six peer-reviewed journals.

In 2019, Williams was awarded a Fellowship for Excellence in Teaching grant from the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation and Course Hero. He holds a bachelor’s degree from Coastal Carolina University and a Ph.D. from Virginia Commonwealth.

Daniela Arias-Rotondo, Chemistry and Biochemistry

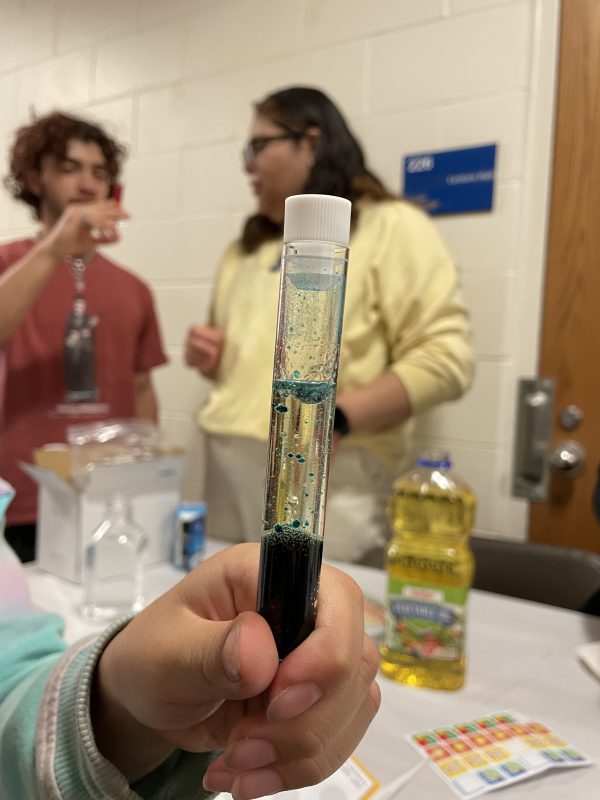

Arias-Rotondo earned a grant valued at $250,000 last year from the National Science Foundation through its Early-Career Academic Pathways in the Mathematical and Physical Sciences (LEAPS-MPS). The LEAPS-MPS grant emphasizes helping pre-tenure faculty at institutions that do not traditionally receive significant amounts of NSF-MPS funding, including predominantly undergraduate institutions, as well as achieving excellence through diversity. She uses the funding primarily to pay her student researchers, typically eight to 10 per term, and bring more research experiences into the classroom.

This year, Arias-Rotondo earned an American Chemical Society (ACS) Petroleum Research Fund grant, which will provide $50,000 to her work while backing her lab’s upcoming research regarding petroleum byproducts. Her lab traditionally develops molecules that absorb energy from light while transforming that energy into electricity. The grant will allow her and her students to take molecules they have designed to act as catalysts and unlock chemical transformations through a process called photoredox catalysis. In this case, those transformations involve petroleum byproducts and how they might be used.

Arias-Rotondo teaches Introductory Chemistry, Inorganic Chemistry, and Molecular Structure and Reactivity, and commonly takes students to ACS conferences. She holds a bachelor’s degree from the Universidad de Buenos Aires in Argentina and a Ph.D. from Michigan State University.