Associate Professor of Psychology Siu-Lan Tan wrote an article (“Why Does this Baby Weep when her Mother Sings?”) for Psychology Today that elucidates an infant’s actions in a You Tube video gone viral. The video shows an infant — Mary Lynne Leroux — emoting deeply to her mother’s singing. Tan suggests the infant’s reactions result from psychological phenomena called emotional contagion and emotional synchrony in combination with the bell-shaped melody of the song itself and just plain wonder. Of course, people (21 million views and counting) are responding more to the magic of the piece rather than its clinical explanation. And the latter in no way diminishes the former. To the question of whether her analysis made the video “any less magical,” Tan wrote, “In my view, it may be even more remarkable and even more compelling to think that what we are witnessing may not just be the power of the human voice and singing — but a window into how deeply and powerfully we are moved by the emotions of those around us, even in our earliest interactions.” It’s an intriguing video and article.

faculty

Kalamazoo College Professor Péter Érdi Earns Award from International Neural Networks Societies

Péter Érdi, K’s Henry R. Luce Professor of Complex Systems Studies, served as the Program Chair for the 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), the premier international conference in the area of neural networks theory, analysis, and application. This year’s IJCNN was held in Dallas, Texas and was attended by more than 500 people.

Professor Érdi, who teaches in K’s departments of Physics and Psychology, was also one of three chairs of the Organizing Committee to receive the Outstanding Service Award from the International Neural Network Society and the Institute of Electronic and Electrical Engineers Computational Intelligence Society, the two leading professional organizations for researchers working in neural networks.

He joined other big names in neural research who received awards at the conference, including Stephen Grossberg (Boston University), considered by many in the field to be the father/inventor of adaptive resonance theory; Terry Sejnowski (University California at San Diego) who works on President Obama’s Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies initiative, which is being compared to the Human Genome Project and the moon landing initiative; and Frank Lewis, a Distinguished Professor at University of Texas Arlington Research Institute who received the IEEE Pioneer in Neural Networks Award for his work in bringing together optimal and adaptive control.

Dream Approaches

Festival Playhouse of Kalamazoo College performs August Strindberg’s A Dream Play in the Nelda K. Balch Playhouse in November. The show opens on Thursday, November 7, at 7.30 PM (“pay-what-you-like-night”). A brief talk-back will follow Thursday’s performance. Additional evening performances are on Friday and Saturday, November 8 and 9, at 8 PM; a matinee concludes the run on Sunday, November 10 at 2 PM. Tickets are $5 for students with an ID, $10 for seniors, $15 for other adults. A Dream Play is part of the Festival Playhouse’s Golden Anniversary season.

The play explores fundamental questions: Why do we exist, and why is life so difficult? The plot surrounds the daughter of the Hindu god, Indra, who leaves heaven to visit humans on earth. In living with humans as a human herself, her mission is to determine why humans suffer. Director Ed Menta says the production will attempt to create a theatre poem by interweaving Strindberg’s text with Festival Playhouse’s staging, performance, and design.

Senior David M. Landskroener, who serves as composer and music producer for the production, says that “creating live sound effects is such an interesting experience because I’m making sound to accompany a dream. Many times while tinkering around with effects I reject my initial thoughts about a certain sound in a scene and try out multiple options that may not at first sound completely congruent with the action onstage, but reflect the idea of associative links found in a dream.”

Before 1901, plays may have contained a dream sequence, but Strindberg created a new genre with a play that is entirely a dream. In the play’s foreword Strindberg wrote: “Everything can happen, everything is possible and probable. Time and place do not exist; on an insignificant basis of reality, the imagination spins, weaving new patterns; a mixture of memories, experiences, free fancies, incongruities and improvisations.”

Given such source materials, one can understand why “It has been a challenge to make all of the 30+ characters come to life,” according to K senior Michael Wecht, assistant director for A Dream Play. “It is my goal, through movement coaching and exercises emphasizing physicality, to help the cast discover each of their roles. This is especially pertinent because most of the actors are playing multiple roles.”

For reservations or more information about Festival Playhouse’s Golden Anniversary season (stay tuned for The Firebugs and Peer Gynt) call 269.337.7333.

Jazz Band Concert Honors Freddie Hubbard

The Kalamazoo College Jazz performs a concert titled “A Tribute to Freddie Hubbard” on Saturday, November 2, at 8 PM in Dalton Theatre, located in the Light Fine Arts building on the Kalamazoo College campus. The concert is free and open to the public. Hubbard (1938-2008) was an American jazz trumpeter whose musical career spanned 50 years.

The 18-member Kalamazoo College Jazz Band will perform selections composed by Hubbard and by other jazz greats with whom he played. Included are: “A Nasty Bit of Blues,” “Ready Freddie,” “Little Sunflower,” “Povo,” “Alianza,” “Red Clay,” and “Out of the Doghouse.” The Kalamazoo College Jazz Band is directed by Professor of Music Tom Evans. Featured performers include Jon Husar ’14, trombone; Ian Williams ’17, piano; Riley Lundquist ’16, tenor sax; Kieran Williams ’16, trumpet; Chris Monsour ’16, drums; and Curtis Gough ’14, bass.

Healthy K

Kalamazoo College has been selected to the Honor Roll of the 2013 Michigan’s Healthiest Employers program. Word of the award came to Ken Wood, the College’s wellness and fitness advisor. The awards and best practices program is presented by Crain’s Detroit Business, MiBiz, and Priority Health to recognize companies around the state whose policies, programs, and culture create healthy employees and healthy workplaces. As an honor roll member, the College will be invited to attend the Healthiest Employers Awards & Best Practices event (January 10, 2014) at DeVos Place in downtown Grand Rapids. After a healthy breakfast, finalists and honor roll organizations will enjoy a panel discussion with the winning companies to learn about their best practices, challenges, and plans for the future.

Professor Emeritus of Physics David Winch Has Died

The Kalamazoo College community is saddened to learn of the death of Professor Emeritus of Physics David Michael Winch, age 78. David, of Taos, New Mexico, passed away unexpectedly October 7, 2013 while riding his bicycle. David taught at the College from 1967 to 2001. Before coming to K he taught at John Carroll University, Clarkson College of Technology, the United States Air Force Academy, and British Open University. He conducted research for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Argonne National Laboratory, and the Desert Research Institute.

Winch was an enthusiastic bicyclist, and was often seen on campus on his bicycle. He usually biked the 13-mile round trip from his home to K. He also loved the out-of-doors, especially mountains, and he co-founded the College’s popular LandSea wilderness first-year orientation program.

In addition to physics, he was deeply involved in science education at all levels. He believed that science is best learned using a hands-on approach, and he believed that science is best learned through collaboration and group work. He was a founding board member of the Kalamazoo Area Mathematics and Science Center, a magnet school for gifted high school math and science students in Kalamazoo County. He also was a teacher and director with ScienceGrasp, a national program that encouraged elementary school teachers to use hands-on science teaching strategies in their classrooms. During his career he received more than $2.8 million in grants on behalf of science education, and he published more than a dozen articles and presentations on physics education for various learning levels. In one of those publications he wrote, “An infant reaches for a brightly colored object; tiny fingers squeeze the object, exploring its shape and texture. The infant shakes the object to see if it rattles and almost certainly puts the object in her mouth. She uses all of her senses to experience the sizes, shapes, colors, sounds, and textures of her world. A child is naturally curious and begins at an early age the lifelong business of learning about this world in which we live. This innate curiosity is perhaps most evident during the period of human development marked by the question ’Why?’ It can be frustrating to deal with a child who wants to know ’why,’ yet it can also be refreshing to have renewed contact with this childlike curiosity. Science tries to answer the ’why’ of the physical world. It is a grand journey, guided by a myriad of questions and a few answers. We, as teachers, are guides in this journey of exploration.” Winch said that the most important element of his pedagogy was to “ask questions and then keep quiet,” and he noted the difficulty of the latter for teachers. And yet the duration of the period of silence following a question, said Winch, is (to paraphrase an aphorism about teaching often ascribed to Socrates) the difference between kindling a flame and filling a vessel.

After moving to Taos in 2002, he served as president of the Upper Las Colonias Neighborhood Association. He loved Taos. He also loved skiing, kayaking, canoeing, He is survived by his wife, Suzanne Winch; children, Michael Winch, Janet McBarnes, Martin Winch, Douglas Winch (Lisa), Kenneth Winch, Robert Kuiper, Shelli Kuiper, Joseph Kuiper (Kim); and 11 grandchildren, two great-grandchildren, many other family and friends. A memorial service in New Mexico will be held at a later date. In lieu of flowers, please make a donation to C.A.R.E. or the American Red Cross.

A memorial service for David will be held Sunday October 20, 1:30 p.m., in Stetson Chapel on the K campus followed by a reception in the Olmsted Room, Mandelle Hall. An obituary appears in the Kalamazoo Gazette.

Kofi Awoonor, Ghanaian Poet, Diplomat, and K Visiting Professor Killed in Nairobi Mall Attack on Sept. 21

Shortly after the first news reports of an attack by armed assailants on the Westgate Mall in Nairobi, Kenya on Saturday Sept. 21, Kalamazoo College administrators received word from the resident director of the K study abroad program at The University of Nairobi that all eight K students in the program were safe and had been instructed to shelter in place with their host families. The students had been in Nairobi for about five weeks at that time.

Two days later, as the mall attack continued, the College offered its students three options: continue the program in Kenya, as scheduled; return to the U.S. immediately and enroll in winter quarter classes at K in January; or return to Kalamazoo immediately and enroll in classes for the fall quarter that had begun Sept. 16. Three students chose to return to K and are now enrolled in fall courses. Five students chose to remain in Nairobi and continue with the program.

K currently has two visiting international students from Kenya on campus for one year. With help from the College, these students were able to contact their immediate family members and learn they were safe and unharmed. K’s longtime resident program director in Nairobi, Lillian Owitti, reported that her family was also safe. She and the visiting students from Kenya, however, have extended family members and friends that were killed, injured, or lost their livelihoods when the mall burned and collapsed.

This senseless and violent attack on innocent civilians has thus far claimed the lives of nearly 70 people, and the livelihoods of countless more. The entire Kalamazoo College community mourns this tragic loss.

The K community also mourns the death of Kofi Awoonor, Ph.D., a lecturer and visiting professor at K in the early 1970s, who was killed during the opening moments of the mall attack.

A teacher, poet, author, and former Ghanaian diplomat, Awoonor was attending the Storymoja Hay literary festival in Nairobi when he visited the Westgate Mall with his son, Afetsi, shortly before the attacks. Afetsi was wounded, but is recovering.

“Kofi Awoonor was a statesman, a poet, and a man of great courage,” said Kalamazoo College President Eileen Wilson-Oyelaran who became familiar with Awoonor and his work in 1970 when she studied at the University of Ghana in Legon where Awoonor taught.

“African poetry has lost an elder statesman, a role model and mentor to so many.” Wilson-Oyelaran read an excerpt from Seamus Heaney’s poem “The Cure at Troy” in Awoonor’s honor at the all-faculty meeting on the K campus two days after his death.

Awoonor visited Kalamazoo several times in the early 1970s, lecturing and teaching at both Western Michigan University and Kalamazoo College. He taught a course on African literature at K.

“That course changed my life,” Gail Raiman ’73 said recently, upon learning of Awoonor’s death. “It was rich with strange and scintillating imagery and a profoundly different approach to writing and to life.”

Awoonor’s book of poems Night of My Blood and his novel This Earth, My Brother (both published in 1971) were especially memorable, according to Raiman.

“None of us previously had this informed and incredible access to African literature, nor the benefit of having one of Africa’s top literary figures as our teacher. We had no idea how lucky we were.”

Raiman said she followed Awoonor’s career after he returned to Ghana, where he was imprisoned by the country’s military government and, after his release, became a diplomat, continuing to write and inspire.

“It was with profound sadness that I learned of his death,” she said. “May we continue to be challenged and inspired by his many gifts.”

Two other writers with strong connections to Kalamazoo College were also in Nairobi attending the same Storymoja Hay Festival during the attacks.

Writer and photographer Teju Cole ’96 wrote in a Sept. 26 blog post for The New Yorker that he was on stage at the festival taking questions from the audience during the first hour of the mall siege, unaware of what was taking place about a mile away. Two days later, Cole attended an impromptu memorial for Awoonor and read Awoonor’s short poem, The Journey Beyond.

“The most resonant moment of the evening was the least anticipated,” wrote Cole about the memorial. “Someone had made an audio recording from the master class that Awoonor had given at the Festival on Friday.” Cole wrote that the audience listened to Awoonor talking “with both levity and seriousness” about death and dying.

“At seventy-nine, you must know—unless you’re an idiot—that very soon, you should be moving on. An ancient poet from my tradition said, ‘I have something to say. I will say it before death comes. And if I don’t say it, let no one say it for me. I will be the one who will say it.’”

Also attending both the Storymoja Hay festival and the memorial gathering for Kofi Awoonor was Ghanaian born Jamaican poet and writer Kwame Dawes. Dawes was a cousin to Awoonor and series editor of the African Poetry Book Fund which is set to publish Awoonor’s latest collection, Promises of Hope: New and Selected Poems in 2014.

Like Awoonor in the early 1970s, Kwame Dawes was a visiting lecturer at both WMU and K, in 2008.

He filed his report on Awoonor’s life and death on the Wall Street Journal website on Sept. 22, the day after Awoonor’s death. In it, he wrote:

“Those who will carry the heaviness of loss will be his immediate family beginning with his son who was shot and wounded in the Mall and who had traveled to Kenya to be with his father and to support him. There are other siblings, other cousins, other extended families, thousands of past students, and a Ghanaian nation that will mourn his death deeply.”

Kofi Awoonor earned a B.A. from University College of Ghana, an M.A. from University College, London, and a Ph.D. in comparative literature from State University of New York at Stony Brook. His books of poetry also include Rediscovery and Other Poems (1964), Ride Me, Memory (1973), The House by the Sea (1978), The Latin American and Caribbean Notebook (1992), and Until the Morning After (1987).

Drawing on his Ewe heritage, Awoonor translated Ewe poetry in a critical study titled Guardians of the Sacred Word and Ewe Poetry (1974). Other works of literary criticism include The Breast of the Earth: A Survey of the History, Culture, and Literature of Africa South of the Sahara (1975).

In addition to teaching at Kalamazoo College in the early 1970s, Awoonor served as chairman of the Department of Comparative Literature at SUNY Stony Book. After returning to Ghana in 1975 to teach at University College of Cape Coast, he was imprisoned without trial for his suspected involvement in a coup d’état. After his release, he wrote about his time in jail in The House by the Sea and resumed teaching.

Awoonor went on to serve as Ghana’s ambassador to Brazil and Cuba during the 1980s, and as ambassador to the United Nations from 1990 to 1994. He published Ghana: A Political History from Pre-European to Modern Times in 1990 and Comes the Voyager at Last: A Tale of Return to Africa in 1992.

Seniors Present Chemistry Research

Three Kalamazoo College seniors presented their Senior Individualized Project (SIP) research at the Midwest Symposium on Undergraduate Research. The event took place at Michigan State University on Saturday, October 5. The students, their presentation titles, and where they did their SIP:

Three Kalamazoo College seniors presented their Senior Individualized Project (SIP) research at the Midwest Symposium on Undergraduate Research. The event took place at Michigan State University on Saturday, October 5. The students, their presentation titles, and where they did their SIP:

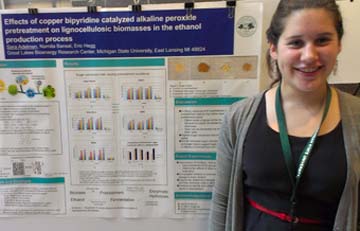

Sara Adelman’s poster (see photo) won the Outstanding Poster Award for Biochemistry. It was titled “Effects of Copper Bipyridine Catalysed Alkaline Hydrogen Peroxide Pretreatment on Lignocellulostic Biomass in the Ethanol Production Process.” Adelman did her research with Professor Eric Hegg ’91 at Michigan State University.

Geneci Marroquin presented a poster titled “Reactions of Cobalt(II) and Nickel(II) Complexes Containing Binucleating Macrocyclic and Pyridine Ligands with Carboxylic Acids: Formation of Binuclear Co(II), Co(II)Co(III), and Ni(II) and Tetranuclear Co(II) and Ni(II) Complexes.” Her research was done in the laboratory of Professor Thomas J. Smith at Kalamazoo College.

Kendrith Rowland conducted his research in the laboratory of Professor Catherine Murphy at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Rowland’s poster was titled “High Sensitivity Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) Nanoplatform Based on Gold Nanoparticle Aggregates.”

Kalamazoo College Professor of Chemistry Jeffrey Bartz gave an invited talk at the symposium. That talk, “Detecting Cartwheels and Propellers by Velocity-Mapped Ion Imaging,” highlighted the SIP work of Ryan Kieda ’09, Masroor Hossain ’12, and Nic West ’12, as well as the research of Amber Peden ’11, Aidan Klobuchar ’12, Kelly Usakoski ’14, Braeden Rodriguez ’16, and Myles Truss ’17.

Endowed Six Help Extend Excellence and Impact

In late September K announced the launch of the public phase of its $125 million Campaign for Kalamazoo College (of which $84 million has been raised). The excellence and impact of a K education derives directly from the quality of its faculty. Toward the end of ensuring that excellence and impact, the campaign is already having an effect–specifically by supporting six new endowed professorships (a final goal of the campaign is to fund 10 endowed professorships). Five of the six positions have been appointed. The sixth will soon be named. The five appointees are:

The Arcus Social Justice Leadership Assistant Professor of Anthropology — Adriana Garriga-López

The Arcus Social Justice Leadership Associate Professor of Political Science — John Dugas

Lucinda Hinsdale Stone Assistant Professor of Religion — Taylor Petrey

James B. Stone College Professor of Theatre Arts — Ed Menta

Edward and Virginia Van Dalson Professor of Economics and Business — Ahmed Hussen

Endowed faculty positions honor outstanding faculty members and provide funds for research and the pedagogical explorations of those professors. Such positions suggest the academic prestige of Kalamazoo College. New endowed faculty positions allow faculty expansion in critical academic fields. And because the money for such positions comes from earnings from the principal of endowed gifts, these professorships remove stress on the College’s operating budget, enabling the College to apply the savings that result to educational innovations and opportunities which are often as unforeseen as they are important. The ultimate beneficiaries are Kalamazoo College students and the nonpareil learning experiences they forge with their professors. The Campaign for Kalamazoo College seeks to raise $62 million in endowment monies to support not just new faculty chairs, but also scholarships for students and improvements to the programs that constitute the K-Plan.

Transition Fan

Professor of Physics Jan Tobochnik is a self-described “big fan” of phase transitions–solids to liquids; liquids to gas; magnetic to non-magnetic; the fall of the Soviet Union. Just a few examples of spectacular phase transitions, and phase transitions are “always interesting,” says Tobochnik. Also, some systems act like they are at a phase transition, such as perhaps the neural firings of the brain. In particular, he’s intrigued by the physics associated with the very moment of change–a period of “criticality” at which all scales of behavior are important.

So it’s no surprise that for the next three years his research (supported by a grant from the Petroleum Research Fund) will involve reproducing experimental data and generation of new data through computer models of melting. Wait…melting? Surely a phenomenon as long observed as this (just set an ice cube on the counter) is thoroughly known to science. Not so, says Tobochnik. “Science has no comprehensive theory for three-dimensional melting,” he says. “Consider that ice cube on the counter–we know it melts from the outside in, but we only know the mechanisms for melting related to surfaces or defects. Absent a surface or a defect, we don’t know how a material melts. We have no general theory, which, in the case of new materials, makes the prediction of melting points and other properties unreliable.”

Two very recent–and painstaking–experiments (one at Harvard, the other in China) managed to explore the phenomenon of melting when there are no surfaces or defects by using colloidal spheres suspended in a fluid. The result was some fascinating new data. But the experiment is extremely difficult to set up, making replication, confirmation, and extension of the data a problem. Tobochnik’s grant will enable his lab to work with the Harvard group to set up a computer modeling simulation of the experiment. That modeling will confirm and, hopefully, provide new knowledge of melting in three dimensional substances.

The grant will fund two students in Tobochnik’s lab for three consecutive summers. They may, or MAY NOT, be physics majors doing SIP work. “Many times I prefer to provide significant research experiences to younger students, including first-years,” Tobochnik says.