With the International Day of Women and Girls in Science on February 11, Kalamazoo College commonly celebrates the accomplishments of scientists such as Rachel Kramer ’23.

The day, first marked by the United Nations in 2015, encourages women scientists, and targets equal access to and participation in science for women and girls. Such a day is desired because U.N. statistics show that fewer than 30 percent of scientific researchers in the world are women and only about 30 percent of all female students select fields in science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) to pursue in their higher education. Only about 22 percent of the professionals in cutting edge fields such as artificial intelligence are women, and representation among women is especially low professionally in fields such as information and communication technology, natural science, mathematics, statistics and engineering.

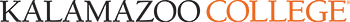

However, Kramer—a biochemistry major with a concentration in community and global health and a minor in Spanish—is bucking that trend. She will attend the Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine in July 2023. Plus, she completed 10 weeks of research last summer investigating health inequities in Ghana, Africa, while collecting data and researching Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD’s) for her Senior Integrated Project (SIP).

The lead up to her SIP opportunity began two summers ago when she decided to get into volunteer work abroad through International Volunteer Head Quarters (IVHQ). At that time, she spent two weeks in Ghana, where she performed health care outreach by providing wound care to people in remote areas under the supervision of local health professionals.

While she was there, she saw people with parasitic diseases which she later found out were considered to be NTD’s. Such diseases are of special interest to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO). In fact, the two organizations have a roadmap for eradicating NTD’s by 2030, which involves working with local researchers in endemic regions to collect data to inform policy to better protect and serve the people affected by NTD’s.

“I saw children 5 years old and younger with these ulcers half an inch deep in their ankles and feet,” Kramer said. “It struck me and I knew that these things shouldn’t be happening.”

Even before returning to Michigan, Kramer knew she wanted to go back to Ghana and develop her SIP there as her way of helping to solve the health issues she witnessed. She just didn’t know what might provide that opportunity.

After several random conversations asking people, including K alumni, about anyone doing research there, Kramer reached out through Twitter to Blessing Ankrah, a researcher with the NeTroDis Research Group, a non-governmental agency at the University of Energy and Natural Resources (UENR) in Sunyani, Bono Region of Ghana.

“Two weeks later, she ended up responding and said she’d be happy to collaborate,” Kramer said. “We started talking on Zoom and WhatsApp, and she decided to have me work on a project where they were updating the prevalence rates of two neglected tropical diseases called schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis.”

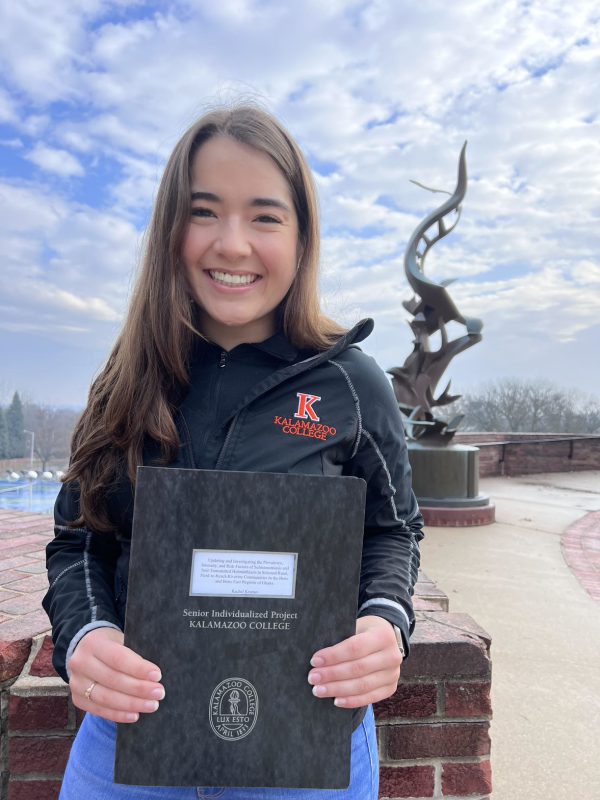

According to the CDC, schistosomiasis parasites live in some types of freshwater snails, and humans become infected when their skin touches contaminated water. Health-care professionals diagnose schistosomiasis through urine and stool samples. Within days of becoming infected, patients typically develop a rash or itchy skin. Fever, chills, cough and muscle aches can begin within a month or two of infection. If left untreated, this disease can become fatal.

Soil-transmitted helminthiasis, the CDC says, targets human intestines as parasites’ eggs are passed in feces. If an infected person defecates outside—near bushes, in a garden or on a field, for example—parasitic eggs are deposited on soil. People can ingest the parasites when they eat fruits and vegetables that have not been carefully cooked, washed or peeled. Some infections can cause a range of health problems, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, blood and protein loss, rectal prolapse, and slowed or stunted physical and cognitive growth. Similar to schistosomiasis, if untreated, this disease can become fatal.

Ankrah became a host mom to Kramer as both worked on the project to update and investigate the relevance, intensity and risk factors of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in selected rural and hard-to-reach communities in the Bono and Bono East regions of Ghana. The opportunity was funded by the Hough SIP Grant and the Collins Fellowship through Student Projects Abroad (SPA) funding, both of which were through Kalamazoo College. .

“This summer was an experience where I was not only a researcher, but I was also a student and a family member,” Kramer said. “Blessing was able to show me what the food was like, what the people were like, what the culture was like and it was just an amazing life experience.”

Yet research definitely remained the purpose of her visit. For the first three weeks, it was necessary for the researchers to perform paperwork during business hours to ensure the ethical approval of the project by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) committees at UENR. During the evening hours, Ankrah introduced Kramer to her family and friends including host brother Lord Owusu Ansah; the university’s president, vice president and dean of science; and regional hospital leaders.

When the five-week field work began, Kramer and her fellow researchers traveled to eight isolated communities that had as few as five and as many as 200 residents to collect socio demographic and qualitative data along with urine and stool samples.

“We would get up at 4:30 a.m. and ride in a packed van for about three hours,” Kramer said. “When we arrived to the communities, many times we would have to walk a distance with all of our gear. Some of these communities were only a few households and are located so far from public roads, and that’s why these diseases are considered neglected. It took us two hours to walk to one of the communities on foot and there was no way to get there with a car. Since there are so few people living in these remote places, there’s no way the government would fund roads to these communities.”

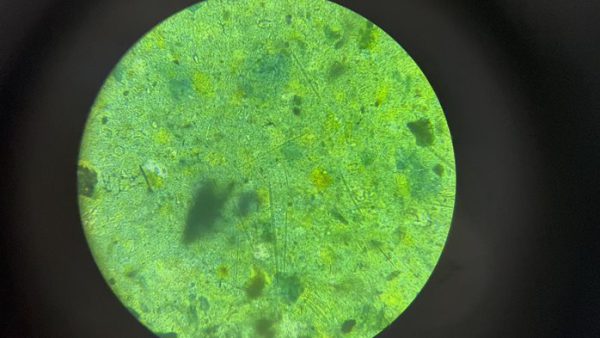

After traveling back to the UENR campus from the field, the researchers stored their samples in freezers before resting for a few hours and then returning to the lab around 7 p.m. in the evening when they analyzed up to hundreds of samples. The immediacy was imperative despite their long days because the urine and stool samples would go bad within 24 to 48 hours.

After the field work, Kramer’s biggest roles were inputting data, helping with the preparation of samples, and microscopic analysis of the specimens.

“Once we got our data from all eight communities, we compiled all of it and I worked with a data analyst at the university who helped me compile it to get our overall prevalence rates and associate the risk factors to the positive cases,” Kramer said.

This work became the basis for her SIP.

“Now that my written SIP has been submitted, all that’s left to do is present my SIP at the annual Chemistry and Biochemistry SIP Symposium during the spring trimester and then wait to find out whether I attain honors from the faculty for my work,” Kramer said. “So many people questioned why I decided to do something so big for my SIP since I have already been accepted to medical school. But just because I have been accepted doesn’t mean I need to take a step back, so I decided to pursue a passion instead. I did this because I have seen these diseases firsthand and how disproportionately they affect people of low socio-economic status in tropical regions. I was emotionally driven to take part in the global movement to end the neglect. Additionally, I knew that this opportunity would enhance my cultural competence which can help me be a better physician to people in the future. Eventually, I’d like to be a study clinician in similar studies and even create the policies that can protect and serve people. With this foundational-level research under my belt, I am motivated to continue my research focus on NTD’s in medical school.”

And this might not be the last of her research outside of medical school.

“I’m still in contact with my host mom,” Kramer said. “I have a number of people in Ghana I text every week just to talk about various things like the projects they’re working on. Currently, they have two new projects that are going to be funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation regarding an NTD called Onchocerciasis, which is transmitted through biting black flies. I asked Blessing if it is possible for me to work remotely while I’m in medical school on those projects, and she said I probably could, but it is also possible that I could go back to Ghana during this upcoming summer to join their new projects in projects in person. Overall, I loved being abroad and how it opened up my eyes to the world and cross-cultural differences. Being a future physician, I was introduced to the atrocities of Neglected Tropical Diseases and I saw just how invaluable being a part of the team that is working to end the neglect really is.”